“Too Much Botox,” People Are Shocked by 60-Year-Old Sandra Bullock’s Appearance in New Video

Thanks to modern technology, scientists manage to find new details on paintings of the past. Some paintings reveal hidden images under a layer of paint, while in others, art historians find hidden characters. However, some questions can’t be answered even with the help of sophisticated technology. We decided to find out what discoveries can make us look at famous paintings in a different way.

In the large convex mirror at the center of the composition are reflected not only the backs of the two portrayed figures, but also two men entering the room, one of whom raises his hand in greeting.

Immediately above the mirror is van Eyck’s Latin signature: “Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434” (“Jan van Eyck was here 1434”). It is speculated that the men in the mirror are van Eyck himself with a companion or servant. The mirror functions as a portal between the pictorial world and reality, where the artist documents not only the portrait but also his own presence as a witness to the scene.

French scientist Pascal Cotte revealed through his investigation that Leonardo painted the work in three separate stages.

Initially, it was a simple portrait of Cecilia Gallerani without any animal — her hands were positioned differently. In the second stage, the artist added a small grey ermine, and in the final version, he replaced it with the larger, symbolically charged white ermine we see today.

X-ray studies confirm that the ermine was painted using the lead white ground layer, indicating it was part of the original conception. This evolution transforms the painting from an intimate portrait into a complex allegorical work, where the ermine simultaneously symbolizes Cecilia’s purity and the emblem of her lover Ludovico Sforza, who was nicknamed “the white ermine.”

When people first saw Van Gogh’s painting Irises, they were absolutely delighted. The canvas was filled with air and colors. One critic even remarked that the artist was able to truly understand and convey the exquisite nature of flowers. Nowadays, this work also makes a strong impression. However, as it turns out, we see it differently than the master’s contemporaries.

A recent detailed study has shown that the irises were originally a deep purple color. To get the right shade, Van Gogh mixed blue and red colors. Unfortunately, the pigments in the latter were sensitive to light and degraded over time. This is how the irises acquired their present blue color.

Only about 30 paintings belong to the brush of the famous master (at least that’s what art historians believe), and recently this list has been reduced by one more painting. Experts have long assumed that the Girl with a Flute could have been created by another artist, and recently their suspicions have been confirmed.

Unlike his other paintings, this one was not painted on canvas, but on a wooden board. A team of curators, restorers, and scientists conducted a detailed study and found that the technique of applying paint is slightly different and looks more careless. The unknown artist was clearly familiar with Vermeer’s style and used similar materials.

Perhaps the master did have an apprentice, although it was previously thought that he worked alone. Another option is that the painting could have been painted by Vermeer’s eldest daughter, Maria, who at that time was between 15 and 20 years old. Or Girl with a Flute is the result of the mutual work of the master and another artist.

The artist created this painting in 1884, even before he started using his famous painting style, and 3 years later the master decided to tweak the work using a new technique. It was Seurat who began to apply pure colors to a canvas in small dot strokes, without mixing them on the palette. The painter assumed that at a distance, the dots of paint would optically blend, creating the desired image.

This idea was inspired, among other things, by the work of chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. This is probably why Seurat painted 6 pipes in the background, making them look like paintbrushes. These pipes belonged to a factory that produced candles using the process invented by Chevreul. In this way, Seurat paid tribute to the chemist.

Previously, art historians could only guess how exactly the artist worked on his famous painting. But recently the canvas was scanned with a special X-ray machine and found traces of calcium under the strokes.

It turned out that Rembrandt first made several sketches on the canvas using paint with a high content of chalk, and it was these lines that the device was able to detect. Thus, initially the exquisite helmet of one of the men was decorated with feathers, but later the artist abandoned this idea.

One of Claude Monet’s most famous paintings depicts several women. However, the model for all the ladies was the artist’s future wife, 19-year-old Camille Doncieux. Although the painting irritated critics, it was later recognized.

It’s not known why Monet decided to use only one model for all the characters. Perhaps this was his way of expressing his love for his beloved, or to capture the versatility of her nature on canvas. Other researchers suggest that the master wanted to experiment with the effects of light and color and test how they affect the same face and body.

For more than 100 years, art historians have been debating whether Vermeer used a camera obscura or not. The fact is that the master’s paintings are characterized by perfect perspective, superb composition, and an amazing sense of light.

In addition, Vermeer worked perfectly with highlights, and some objects in the foreground seem blurred (as seen in the painting The Lacemaker). The camera obscura, a device that allows you to get an optical image of an object, captures these nuances better than the human eye.

In Vermeer’s time, many artists were familiar with this invention, but no one wanted to admit that they used it. Otherwise, the artist’s talent would have been immediately questioned. There is no evidence that Vermeer owned a camera obscura, although his good friend and neighbor was the scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who created excellent microscopes and lenses for his time. So, the artist could turn to him for help.

Some researchers are sure that Vermeer did not use a camera. 13 of his paintings have tiny holes in the canvas, which the painter most likely used to determine the exact perspective. Anyway, the question of the presence of a camera obscura in Vermeer’s studio is still open.

The painting Madonna della Vittoria was created in 1496. At that time, the well-established trade routes between Europe and Southeast Asia didn’t exist. However, in the upper left corner, you can see a bird that looks very much like a yellow-crested cockatoo. This species used to inhabit some islands in Indonesia (now it’s classified as endangered). Given the cockatoo’s natural pose, it was probably painted from life.

But the researchers were concerned with one question: how could the bird get from Indonesia to Europe? Most likely, the cockatoo reached its destination along the Silk Road, and this journey could have taken many years. But since these parrots live up to 60 years, this journey was quite possible. Or the bird traveled to its new habitat via India. Either way, the story of the cockatoo’s wanderings would make a good story.

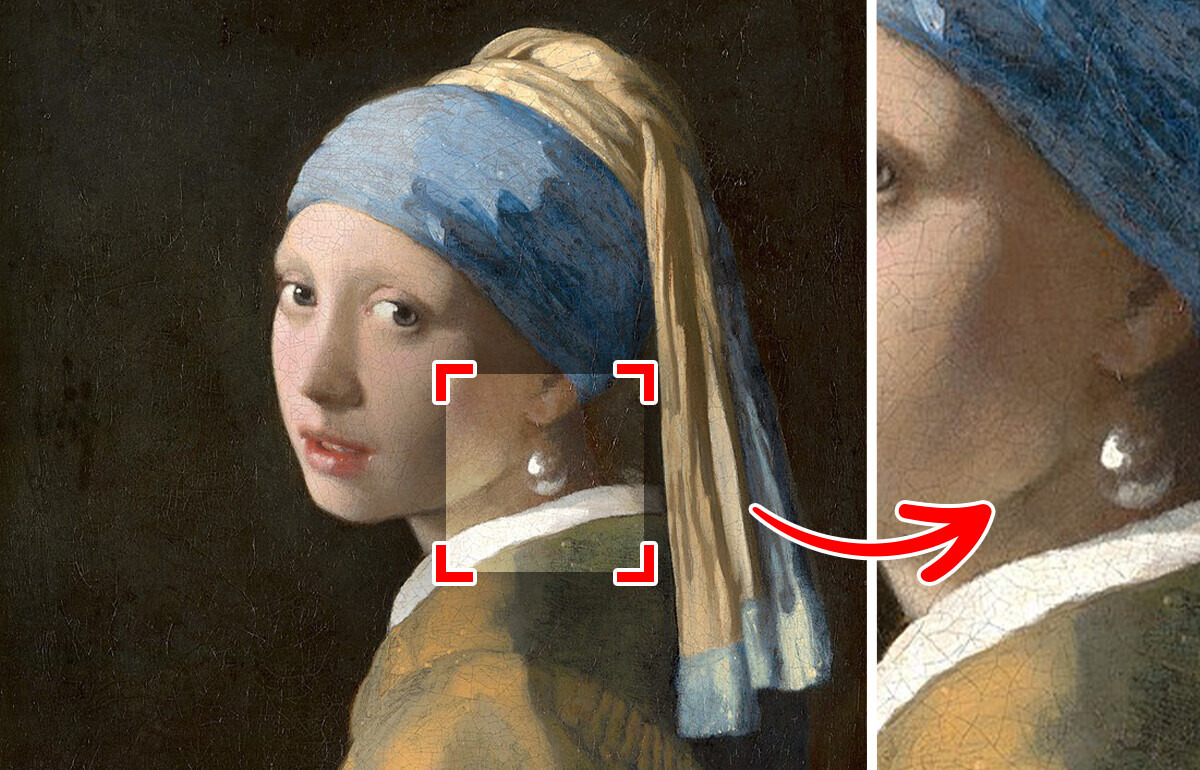

Art’s most famous “jewel” may not actually be genuine. The Mauritshuis Museum confirms that the pearl is too large to be real — it’s probably an imitation made of glass with a matte varnish or even a product of Vermeer’s imagination.

The artist painted it with just two strokes of white paint: one at the bottom to reflect the collar and a thick dab at the top. There is nothing more — not even a silver hook is visible. Despite the fake pearl, the real luxury material in the painting hides in the turban — the ultramarine made from ground lapis lazuli was more expensive than gold.

In the small mirror on the back wall are reflected the upper portions of the bodies of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana. This detail is at the center of one of art’s greatest mysteries — whether the mirror reflects the royal couple standing in the viewer’s position posing for a portrait, or their image from the canvas on which Velázquez is working.

Different theories offer different explanations, but all agree that the mirror transforms the painting into a complex game with reality, where we, the viewers, take on the role of the royal family and participate in the work itself.

X-ray analysis from 2015 at the Tretyakov Gallery revealed two earlier paintings beneath the black surface.

The original composition is Cubo-Futurist, while the one directly beneath the “Black Square” is proto-Suprematist with bright colors visible through the cracks. What appeared to be the “zero point” of painting actually contains multiple artistic experiments, transforming our understanding of this revolutionary work.

The hidden layers reveal that Malevich’s path to abstraction was not a sudden leap but a gradual evolution, with each layer representing a different stage in his artistic development. These discoveries transform the “Black Square” into a palimpsest of modern art — a canvas that holds the memory of its own creation.

And these cinematic moments reveal an intricate web of artistic inspiration beneath the surface. What initially seems like a simple film scene often carries deeper cultural references, where directors weave visual homages to masterpiece paintings into their storytelling. These deliberate artistic connections create layers of meaning that transform ordinary movie sequences into sophisticated dialogues between cinema and classical art.