Mean People Asked Her to Stop Posting Photos Because of Her Appearance, but She Continued and Became a Model

Ever noticed how your belly seems to swell after a meal, tighten during stress, or steadily expand despite your best efforts? You’re not alone. Belly fat isn’t just about what we eat—it’s a complex combination of biology, habits, and even hidden cell types that science is only beginning to understand. Whether it’s a temporary bloat from gas and water retention or a more stubborn accumulation linked to stress or metabolic dysfunction, each belly type tells a different story about what’s going on inside.

Disclaimer: This content is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical concerns or before making changes to your health regimen.

This belly balloons after meals but shrinks again once the gas or fluid moves on. Up to one-quarter of otherwise healthy adults report occasional abdominal distension that’s traced to excess intestinal gas, rapid eating, food intolerances (lactose, FODMAPs), constipation, or menstrual water retention. Because the added volume is mostly air + fluid—not fat—people often see the waist flatten within days by slowing their eating, limiting carbonated or highly-processed foods, increasing fiber gradually, walking after meals, and treating any underlying gut issue.

Chronic psychological or physiological stress keeps cortisol levels chronically elevated, which can contribute to the development of cortisol belly—a specific type of belly fat linked to prolonged exposure to high cortisol. While cortisol helps the body manage stress, regulate metabolism, control blood sugar, and reduce inflammation, too much of it over time can disrupt these systems.

Persistently elevated cortisol can stimulate appetite, promote fat storage—especially in the abdominal region—and lead to noticeable weight gain. This pattern is often seen in individuals dealing with long-term stress, those taking corticosteroids, or people with hormonal conditions such as adrenal tumors. In more severe cases, it may be a sign of Cushing’s syndrome. Managing cortisol belly typically involves treating the root cause of cortisol dysregulation, whether that’s medical, lifestyle-related, or both.

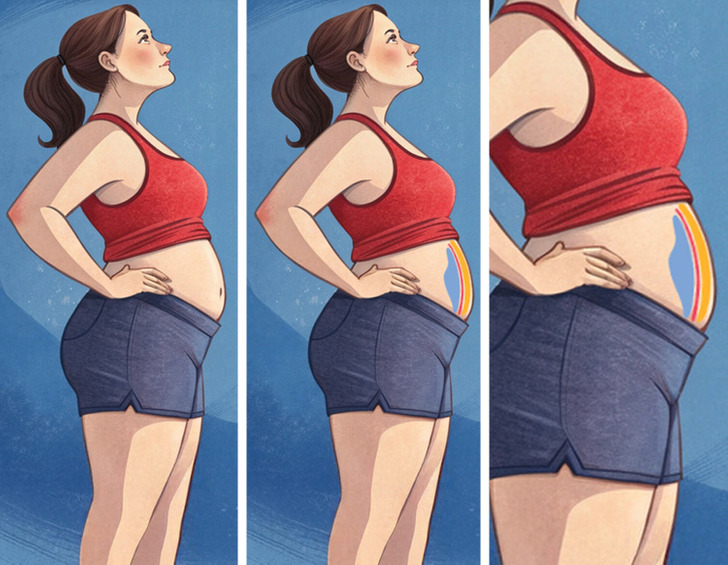

A firm, deep belly that pushes the waist above ≈ 88 cm (35 in) for women or 102 cm (40 in) for men is a key sign of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that significantly raise the risk for type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Also known as insulin resistance syndrome or syndrome X, metabolic syndrome is diagnosed when a person has the following risk factors:

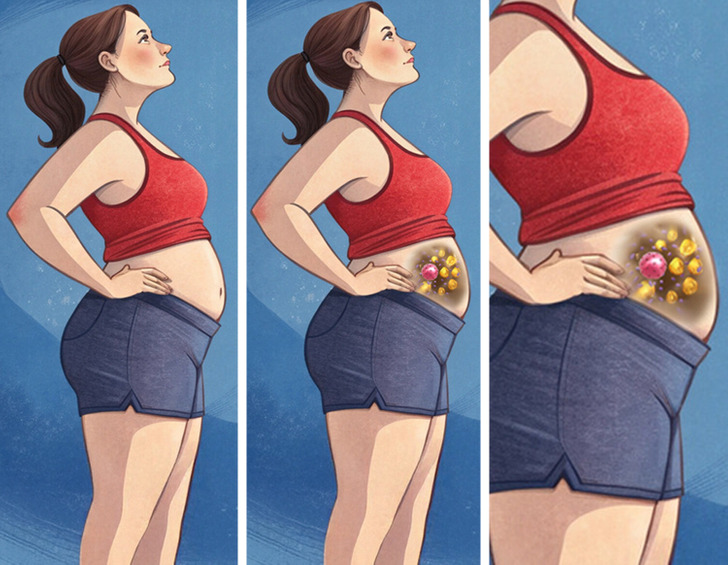

What if the secret to tackling obesity wasn’t just about how much fat we have, but what kind of fat we carry?

In a groundbreaking study published on January 24 in Nature Genetics, scientists unveiled the discovery of previously unknown subtypes of fat cells—each with unique roles and potential links to inflammation and insulin resistance. These findings suggest that our fat isn’t as uniform or passive as once thought, and understanding its inner diversity could transform how we address weight-related diseases.

“Finding these [fat] subtypes is something very surprising,” said Esti Yeger-Lotem, a computational biology professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. “This opens up all kinds of potential future work.”

Once considered a simple storage system for excess energy, fat tissue is now seen as a dynamic, communicative player in the body’s metabolic orchestra. According to the study’s authors, fat cells influence a range of vital processes—from appetite regulation to blood sugar control—by signaling to organs like the brain, muscles, and liver.

“If something is wrong there,” Yeger-Lotem added, “it affects other places in the body.” This complexity makes the recent discovery of fat subtypes all the more important. It paints a richer picture of fat as a multi-functional organ, not just an energy bank.

We’ve long known that visceral fat—found deep in the abdomen—carries greater health risks than the more superficial subcutaneous fat. The new research may help explain why. By mapping out a “cell atlas” of adipocytes (fat cells) as part of the Human Cell Atlas project, researchers identified various subtypes with specialized functions

Among them:

The study also found differences in the newly identified fat cell types depending on where they were located. Unconventional adipocytes in visceral fat appeared more likely to interact with the immune system than those in subcutaneous fat, said Esti Yeger-Lotem. This connection to immune cells suggests these subtypes may contribute to visceral fat’s proinflammatory nature, helping explain why belly fat is linked to poorer health.

If these fat subtypes can be linked to human disease, understanding how they work could “help us fight inflammatory processes,” Yeger-Lotem said. That could potentially help doctors predict the risk of insulin resistance in people with obesity, assuming all the dots connect, she added.

Nutritional sciences professor Daniel Berry noted that the study had a relatively small sample size and only suggests, rather than confirms, that these fat cells have unusual functions. Still, “these insights highlight the importance of understanding fat depots’ unique behaviors to develop targeted treatments for obesity and related diseases,” he said.

This discovery highlights just how much we still have to learn about the complexities of the human body. This new discovery reinforces the fascinating idea that science is always evolving, and there’s still so much to uncover about the human body. To reveal things you may not know about your body, check our article about it!

This new research is eye-opening—but here’s the good news: your body has the power to push back. Coming next, we’ll show you 10 simple moves that target this fat and help you feel amazing again.